TikTok Is Watching You – Even If You Don’t Have an Account

I submitted a request under the GDPR, and was shocked to see what data the platform had been recording.

By Riccardo Coluccini – January 21, 2021, 2:59pm

This article originally appeared on VICE Italy.

2020 was TikTok’s year. Although the social media platform was already popular by late-2018, nothing could have boosted its user base faster than our thirst for distraction from the imminent collapse of society. And if all press is good press, TikTok certainly benefited from media attention in 2020, taking centre stage in the geopolitical struggle between China and the US.

Suddenly, everyone cared about what data was being collected by TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance. But despite the Trump administration’s claims that China might be spying on you via your favourite entertainment app, there is no evidence that your data is less safe in the hands of a Chinese company than in those of the US-based “usual suspects”, like Facebook and Amazon. In fact, in July of 2020, the European Court of Justice struck down the EU-US privacy agreement known as Privacy Shield, on the grounds that US national security laws endangered EU citizens’ data.

In light of all this, I wanted some clarity. Taking advantage of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), I asked TikTok to send me all the data they had on me. Anyone in the EU can do this – here is the template I used, and the email address you should send it to.

I’ve never actually created a profile on TikTok. If you open the website on your browser, you can scroll through content without signing up, although certain features – like commenting, following accounts and uploading content – can only be used with a profile. Some users (like me) can also browse the app without an account, while others are required to sign up. TikTok did not reply to our request for comment about this discrepancy. If you do have an account, you can follow these instructions to download your data.

Even though I never signed up, I used the platform briefly – for about two months – but almost daily. As my data later showed, I viewed about 30 videos a day. A sizeable amount, but still below average: the typical user spends about 46 minutes a day on the platform, and most videos are 15 seconds long, coming out at roughly 184 videos.

When you don’t have an account with a company, they often claim they can’t identify your data because they can’t verify the person making the request. And TikTok did initially reject my request. “Unfortunately, we are unable to locate an account associated with the email address,” they replied. They asked for more details, such as a username or “any other e-mail address or phone number that has been used to sign up for an account”.

However, TikTok’s privacy policy states they “collect certain information from you when you use the Platform including when you are using the app without an account”. This “technical information” includes your IP address, mobile carrier, timezone and more.

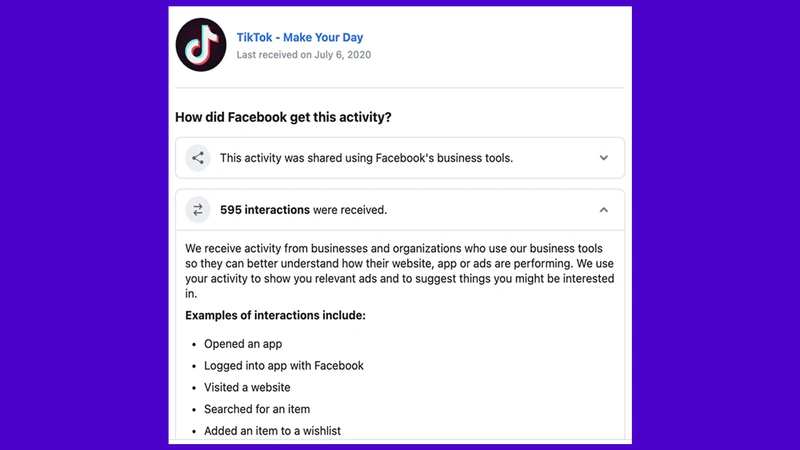

I was faced with a conundrum: TikTok collected data they knew was from my personal device – identified by a specific string of numbers – and therefore mine. But since I didn’t have an account proving my identity, they wouldn’t share it with me. Despite this, they continued to use my data in various ways. For instance, I knew they had shared information with Facebook a whopping 595 times, as Facebook detailed in its Off-Facebook Activity section. This TikTok data is now linked to my personal Facebook profile.

In the end, I proved I was the rightful owner of the data by attaching my IP address to the request, along with a code identifying my iOS device, called the ID For Vendors (IDFV). This code allows app developers to recognise the same device across different apps. For example, if four apps made by the same developer are installed on a single device (like Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram and Messenger), the developer can link all profiles to the same user.

Having received this information, TikTok agreed to send me my data. I was told to visit their Help Centre, select “Report a Problem” and enter the information I mentioned above in the feedback section.

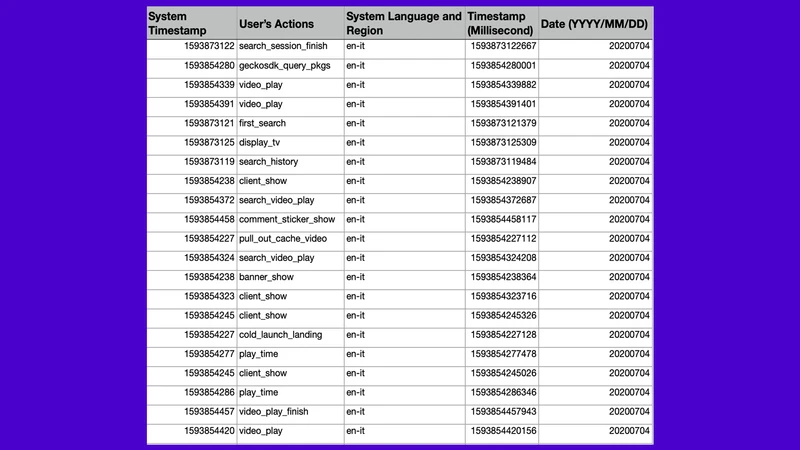

Within two months of my first request, I received two password-protected Excel files and a key to open them in a separate email. The first file consisted of a table with nearly 1,900 rows, logging my whole watch history, one video at the time. The other file, “User Data & Activity”, was a table with 15,886 rows and 24 columns. That’s 381,264 data units recording my short-lived experience on the app, down to the smallest detail.

The video history file came as no surprise. But I was genuinely shocked by the amount of data being tracked and monitored while I was simply watching videos on my phone. The file recorded all my actions in the app and time-stamped them. It also knew my device type and screen resolution, telephone operator, operating system, IP address and another device identification code (different from the one I provided in my request).

For example, it recorded when I was searching or playing a video, plus many other variables that were not explained by TikTok in their privacy section. In 2018, I requested my data from Amazon and obtained a similar table with all the products I searched for, clicked on, bought or saved.

It’s easy to point fingers at TikTok, Facebook or Amazon, but in reality, all apps and websites do this. Every lonely swipe on Tinder at 3AM, every half-watched TikTok video, every spontaneous purchase – they’re all monitored. It’s the nature of the internet we’ve found ourselves inhabiting. Of course, companies don’t need to collect this much data, or store it forever.

Privacy policies often justify data collection by explaining it’s linked to security. Big Tech companies say that keeping track of your activities helps them find and eliminate fraudulent accounts. We’re told companies won’t use the data against our interests, but even so, the information is still stored somewhere, vulnerable to cyber attacks or to privacy policy changes you might absent-mindedly agree to. It can also be (and frequently is) requested by law enforcement during investigations. As the Intercept revealed, the FBI obtained and monitored TikTok user data of dozens of BLM protesters in 2020.

Since TikTok is Gen Z’s platform of choice, people are particularly worried about what happens to the data of underage users. On the 13th of January 2021, TikTok announced that it will change the default setting for users under the age of 16 to private. The decision comes after a 12-year-old in the UK sued the platform, claiming the company uses children’s data unlawfully (under UK law) to power its algorithm.

By now, we all know that social media platforms have vast databases of our activity. It’s up to you to decide if you want to keep using TikTok or not. Just remember – browsing without an account doesn’t make you anonymous.